All of Me Read online

Copyright © Kim Noble 2011, 2012

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by Piatkus

This edition published in 2012 by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

All rights reserved

Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

978-1-61374-470-3

Author’s note

Much of the content of this book takes place in hospitals. Where other patients are mentioned I have used pseudonyms to protect their privacy. Some other individuals’ names have also been changed but their actions are all too true.

Cover design: Rebecca Lown

Author photos: Geraint Lewis

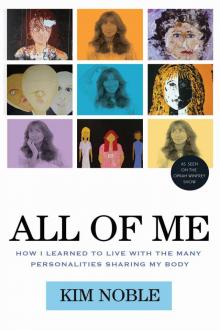

Cover artwork: (clockwise from upper left) The Naming by Dawn, Whatever by Ken, Lucy by Judy, Judy by Judy, I’m Just Another Personality by Bonny

Photos of artwork: Aimee Noble

Title page and part title page artwork: Frieze People at Night by Bonny

Typeset in Swift by M Rules

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to our much-loved daughter Aimee, the sunshine of my life, and our wonderful therapist for her footsteps in the sand.

Contents

Acknowledgements

Prologue: Shattered

PART ONE

1 This is crazy!

2 It wasn’t me

3 Where am I now?

4 My pilot light is going out

5 There’s no helping you

6 You’re in the system now

7 Lights out!

8 What’s it got to do with me?

9 The elves and the shoemaker

10 Can you fix it?

11 I’m not one of them

12 You’ve got ink all round your mouth

13 My own place

14 The psychotic shuffle

15 It’s a crime scene now

16 Please help me

17 This is Aimee

PART TWO

18 Pandora’s box

19 That’s not Skye

20 Where did they all come from?

21 I am not Kim Noble

Epilogue: Action!

Useful Resources

The Artwork in All of Me

About the Author

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Jennifer Todd, Wendy Glaister, Lisa Dixon, Klare Stephens, Anna Tapsell, Campaign Against Pornography, Helena Kennedy QC, Michael Fisher, DCI Clive Driscoll, Lydia Sinclair, Dr Rob Hale, Pearl King, Valerie Sinason and the Clinic for Dissociative Studies, Professor Howard Steele, Saul Hillman, Nancy Dunlop, Ina Walker, Suzanne Haddad, Julia Harrop, Shirley Hickmott, Ami Woods, Debs McCoy, Andrew Simpson at Springfield Hospital, West Thornton Primary and Junior schools, Susan Booth, Fiona Langan and Riddlesdown Collegiate, Palma Black, Sharon Jenden-Rose, John Morton, Henry Boxer, Gillian Gordon, Beth Elliot at the Bethlem Gallery, Malcolm Wicks MP. Thanks are also due to Robert Smith for his continuous support, Jeff Hudson for taking on this difficult challenge, Anne Lawrance and Claudia Dyer for their sensitivity and understanding, the team at Piatkus/ Little, Brown Book Group, Anita and Derek, Saatchi Online for allowing separate personalities to have their own artist web pages and Outside In for accepting us as individual artists. A special thanks to Dr Laine and her husband, Andrew.

In memory of my Mum and to my Dad and his new wife, Jackie. To my sister, Lorraine, and her husband, Lol.

To my family and friends including those sadly lost along the way. To my next-door neighbour and friend, Jean, and in memory of her husband, Stan.

To my invisible friends inside, who at times are too visible!

To all those with or without DID who have emailed me about their hopes and fears.

PROLOGUE

Shattered

Kim Noble was born on 21 November 1960. She lived with her parents and sister and enjoyed an ordinary family upbringing. Her parents both worked and from a very early age Kim was left with a number of childminders – although they weren’t called that in the 1960s. Sometimes it was family, sometimes neighbours, sometimes friends. Communities stepped in to help in those days. Most were kind and loving.

Some were different.

They didn’t look after Kim Noble. They took advantage. They subjected baby Kim to painful, evil, sexual abuse. Regularly and consistently from the earliest age.

Kim Noble was helpless. She couldn’t speak. She couldn’t complain. She couldn’t fight. She didn’t even know that the abuse was wrong.

But she did know it scared her. She knew it hurt.

Yet she was so small, so weak, so dependent on her abusers for so much, what could she possibly do? And then her young, infant mind found a way. If it couldn’t stop Kim’s physical pain it could do the next best thing. It could hide.

At some point before her third birthday, Kim Noble’s mind shattered, like a glass dropped onto a hard floor. Shards, splinters, fragments, some tiny, some larger. No two pieces the same, as individual as snowflakes. Ten, twenty, a hundred, two hundred pieces where before there had been just one. And each of them a new mind, a new life to take Kim’s place in the world. To protect her. At last, Kim Noble was happy.

No one could find her now.

PART ONE

CHAPTER ONE

This is crazy!

Chicago, September 2010. I never imagined the day I would find myself sitting in a television studio on the other side of the Atlantic. I certainly never expected to be invited by the most powerful woman in world media, Oprah Winfrey, to appear during the final season of the planet’s leading chat show. But here I am and, as I take my seat facing Oprah’s chair, I can barely contain my nerves. The most-watched programme in America is about to be filmed and I am that episode’s star guest. And yet, as soon as Oprah sits down opposite, my inhibitions disappear.

Oprah’s studio audience is here to see her. I don’t kid myself that I’m the draw. The hundreds of people packing the auditorium reserved their tickets a year ago, months before I was even booked to appear. But the reason they love Oprah is she asks the questions that the normal American man and woman want to ask. I watch her lean in, gather her thoughts and build up to asking the Big One.

‘Do you remember what happened to you as a child?’

Three hundred people fall suddenly silent. A few sharp intakes of breath. Then nothing, as they all crane forward expectantly for my reply.

‘I remember parts of it,’ I reply. ‘Not any abuse.’

Murmurs buzz around that vast hangar of a room. Oprah looks momentarily thrown. If you watch carefully you can almost see her thinking, I was told this woman had been abused! What’s going on? Backstage you can imagine a huddle of researchers thrown into panic.

Oprah maintains her composure. Then, ever the professional, she rephrases the question.

My answer is the same. ‘No one did anything to me.’ But I know what she means and decide to help her out.

‘I have never been abused,’ I clarify. ‘But this body has.’

And then she understands.

Throughout our interview, Oprah referred to me as ‘Kim’. I don’t mind. I’ve grown up with people calling me that. It’s all I ever heard as a child so it soon becomes normal. ‘Kim, come here’, ‘Kim, do this’. It was just a nickname I responded to, not something to question. Why would I? I didn’t feel different. I didn’t look different. A child only notices they’re out of the ordinary when adults tell them. No one ever told me I was special in any way.

I’ve grown up accepting lots of things that seemed normal at the time. Like finding myself in classrooms I didn’t remember travelling to, or speaking to people I didn’t recognise or employed doing jobs I hadn’t applied for. Normal for me

is driving to the shops and returning home with a trunk full of groceries I didn’t want. It’s opening my wardrobe and discovering clothes I hadn’t bought or taking delivery of pizzas I didn’t order. It’s finding the dishes done a second after I’d finished using the pans. It’s ending up at the door to a men’s toilet and wondering why. It’s so many, many other things on a daily basis.

Oprah found it unimaginable. I doubt she was alone. I imagine millions of viewing Americans were thinking, ‘This is crazy!’

After all, it’s not every day you meet someone who shares her body with more than twenty other people – and who still manages to be a mum to a beautiful, well-balanced teenaged daughter, and an artist with many exhibitions to her name.

To me this is normal.

In 1995 I was diagnosed with Multiple Personality Disorder – now known as Dissociative Identity Disorder, or DID – although it was many years until I accepted it. DID has been described as a creative way for a young child’s mind to cope with unbearable pain, where the child’s personality splinters into many parts, each as unique and independent as the original, and each capable of taking full control of the body they share. Usually there is a dominant personality – although which personality this is can change over time – and the various alter egos come and go. Some appear daily, some less regularly and some when provoked by certain physical or emotional ‘triggers’. And usually, thanks to dissociative or amnesiac barriers that prevent them learning the source of the pain which caused the DID, they all have no idea that the other personalities exist.

This, I was told, is what had happened to Kim Noble. Unable to cope any longer with the trauma of being abused at such a young age, Kim had vacated her body, the doctors said, leaving numerous alter egos to take over. I am one of those alters.

To most of the outside world I am ‘Kim Noble’. I’ll answer to that name because I’m aware of the DID – and also because it’s easier than explaining who I really am. Most of the other personalities are still in denial, as I was for the majority of my life. They don’t believe they share a body and absolutely refuse to accept they are only ‘out’ for a fraction of the day, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. I know how they feel, because for forty years that was me.

I am currently the dominant personality. Simply put, I spend the longest time in control of the body. (On an average day two or three other personalities usually come out and do whatever they do, and in between I return.) I run the household and take primary care of our daughter, Aimee. I pay the bills (even though they’re all in Kim Noble’s name) and make sure we live a normal family life.

I wasn’t always in control, however. As a child I probably only came out for a couple of hours at a time – and perhaps not even every day. As I grew older I seemed to spend more and more time in control of the body, until finally, with the encouragement of our therapists and doctors, I acknowledged the DID and took charge.

Why did I become the dominant one? I don’t know for sure but I think the body needed me to. The woman known as Kim Noble turned fifty in 2010 and I suppose if you look at me I match that age in my knowledge, my experience and my behaviour (although I feel much younger). I’m told that the others who were dominant personalities before me are similar in that respect. But not all of Kim Noble’s alters are like us. Even if they did accept the diagnosis of multiple personalities, many of them would not be capable of running a home. Many of them, sadly, struggle to cope with being alive.

Some of the alters are much younger – frozen at a particular point in time – and several aren’t even female. This seems to surprise people the most. There are three-year-old girls, a little boy capable of communicating only in Latin or French, and even a gay man. Some know their parents; others feel lost. Some are well balanced; others struggle with the scars of their past. One is happy with a lover; some have friends; others are mute, reclusive. Some exist to live life to the full; others have tried to take their own lives.

Our own lives.

Like a lot of people trying to understand DID, Oprah wondered if our multiple personalities were the different facets of Kim coming to life. In other words, one of us is Angry Kim, one of us is Sad Kim or Happy Kim or Worried Kim, and so on, and we come out when the body is in those moods. That’s not how it works. We’re not moods. We’re not like the characters from the Mr Men and Little Miss books – we can’t (in most cases) be defined by a single characteristic. We’re rounded human beings, with happy sides to our personalities, frivolous sides, angry sides, reflective sides.

Oprah couldn’t hide her surprise.

‘Like a normal person?’ she said.

‘Yes,’ I replied, ‘because I consider myself to be normal.’

And I am. When I’m in control of the body my life is no different to anyone’s reading this book. I have the same thoughts, the same feelings, hopes and dreams as the next woman. The only difference is I’m just not here to live those dreams as often as I would like. None of us are.

The different personalities come and go from the body like hotel guests through a revolving door. There are no signals, no signs, no warnings. I’m here one minute and then somewhere else. In between it’s as though I’ve been asleep – and who knows what has happened during that time? I don’t see anything, I don’t hear anything, I don’t feel anything. I have no understanding of what happens when I’m not there. I may as well be in a different country. It’s the same for all of us. We are either in control of the body or completely absent. We’re not witnesses to each other’s actions. As I’ve said, the majority of us don’t even know – or accept – the others exist.

Coming back after a personality switch is like waking up from a nap. It takes a few seconds of blinking and looking around to get your bearings, to work out who you’re with, where you are and what you’re in the middle of doing. The only difference is with a normal nap you soon realise you’re in exactly the same place you went to sleep, whereas I could disappear from my sofa and wake up again at a pub or a supermarket or even driving a car and not have a clue where I’m heading.

It’s not only me who has to come to terms with it, of course. The other personalities find themselves in exactly the same positions and respond as best they can. Shortly before flying over to Chicago I drove into my local petrol station. When I pulled the trigger to turn the pump on nothing happened. Everyone else seemed to be getting fuel so I went into the shop to ask what was wrong.

The lad behind the counter was staring at me in disbelief.

‘I can’t believe you’ve got the nerve to come back.’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘I’m talking about you driving off last week without paying.’ As he spoke he showed me a picture of the car and me – so he thought – behind the wheel.

A few years ago I would have argued and shouted and told him to get some new glasses so he didn’t accuse innocent people. But I knew what had happened. I’d driven there, filled up – and then there’d been a switch. I don’t know who it was but they obviously realised they were in the car, they had no recollection of putting petrol in, so naturally they drove off.

Simple, really – but I could see it looked bad.

Luckily, because I was a regular customer, the guy believed my ‘silly me’ act when I told him I’d just forgotten. Standing there while he went through his little lecture about calling the police next time was utterly humiliating, especially in front of a growing queue of people. But it was less painful than trying to explain DID. I’m not ashamed, embarrassed or shy about it, but sometimes you have to pick your battles.

If that episode had happened before I accepted I had DID, the outcome would have been very different. In fact, I’d probably still be arguing with the cashier now. It wouldn’t matter that it was all captured on film. I would have known I was innocent and fought and fought – just like I always did when people accused me of things I hadn’t done. Sometimes it seemed like my whole life was spent defending myself against crim

es I hadn’t committed. I seemed to lurch from one argument to another, at school, at home, at work or with friends, and all the time I’d be saying the same thing: ‘It wasn’t me.’

You can imagine how confusing life must have been – and how it must still be for the personalities who refuse to accept the truth. Yet somehow I coped. These days it’s the innocent parties who have to deal with us that I feel sorry for. For example, a few years ago I called the police about something and a couple of officers arrived at the house. I went into the kitchen to make them a coffee but by the time I’d returned, they’d vanished. Then I realised the time. It was an hour later. There must have been a switch. Only when I spoke to the policeman later did I learn the truth: another personality had arrived and literally screamed at them to get out of her house! That took some explaining …

I have a thousand stories like this. All the personalities must have. Life is a constant struggle, even when you know about the DID. Sometimes, though, the only thing you can do is laugh. A while ago there was a problem with the computer so the dominant personality at the time drove over to our therapist’s house. Our therapist’s husband is very good at fixing things like that. Unfortunately, when they went to fetch the machine from the back seat of the car, it wasn’t there. Obviously one of the other personalities – not me! – had come out and discovered a computer in the car and had done something with it. Whether they took it to a repair shop or sold it or lost it or just gave it away, we never discovered.

At least I can drive, however. Not all the personalities are so fortunate because many of them are children. A fifteen-year-old called Judy occasionally appears once I’ve parked. From what she’s revealed to our therapist, the first few times were quite scary until she realised the car wasn’t going anywhere. I don’t think the body would allow itself to be endangered by having a non-driver in control of a moving vehicle. Now the worst thing that happens is Judy just hops out and catches the bus home – leaving me to work out where our car is. Every minute of every day brings new adventures.

All of Me

All of Me